By Daniel M. Hurley

INTRODUCTION

While drought and other forms of environmental stresses do not directly cause the onset of civil wars, can they contribute to the outbreak of intrastate conflicts? Concerning the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, scholars have debated the extent to which a severe, multiyear drought lasting from 2006-2010 played a role in the onset of the conflict in 2011. An argument is advanced by a body of scholars (Gleick 2014; Cane et al. 2015) which claims that this drought contributed to the onset of the conflict by acting as a “threat multiplier”, which is understood as an aggravator of existing tensions that can potentially instigate conflict. In particular, by increasing unemployment in the agricultural-sector (Gleick 2014, 331), the drought is attributed with having the subsequent effect of aggravating a variety of socioeconomic grievances already present in Syrian communities prior to the drought’s onset (334). On the contrary, other scholars (Dahi et al. 2017) argue that there is no reliable evidence to support the claim that the drought contributed in any substantial way to the onset of the conflict through its role as a “threat multiplier.”

Given the contrasting views of scholars, the research questions governing this study are: Did the drought contribute to the onset of the conflict, specifically through its role as a “threat multiplier?” If it did, how was its contribution in this way manifested and linked to the onset of the conflict? In this study, I argue that the drought contributed in this way, but its contribution must be understood in terms of a sequence of interconnected, successive events that began with an increase in agricultural-sector unemployment. Specifically, the central argument advanced here is that the drought increased unemployment in the agricultural-sector, and this resulted in the aggravation of preexisting grievances over water scarcity, which assisted in triggering the conflict’s initial protests. Essentially, stemming from the increase in agricultural-sector unemployment, a series of events subsequently occurred that ultimately led to the aggravation of preexisting grievances over water scarcity, which helped to spark the initial protests. Thus, in order to understand how the drought contributed to the conflict’s onset as a “threat multiplier”, it is necessary to comprehend the pathway through which the drought’s contribution manifested itself.

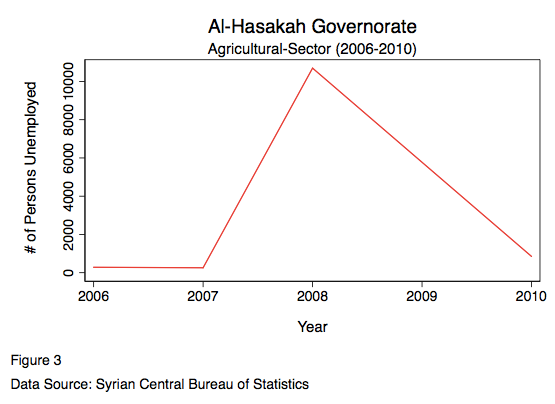

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods, this argument was systematically tested by tracing the drought’s role in the conflict from its initial exacerbation of agricultural-sector unemployment to the eventual role it played in helping to spark the conflict’s onset by aggravating preexisting grievances over water scarcity in specifically the governorate of Daraa, as Daraa’s initial protests sparked the onset of the civil war. From the results of aggregate-level quantitative analysis (see Figures 1 & 2), agricultural-sector employment generally decreased as precipitation decreased in Syria, specifically during the drought period. Additionally, individual-level quantitative analysis (see Figures 3 & 4) exhibits trends that support the internal migration and urbanization claims advanced here. Qualitative data buttresses the quantitative analysis findings, and supports the argument advanced in this study concerning the drought’s contributory role in triggering Daraa’s initial protests—and thus the onset of the conflict—as a “threat multiplier.”

The components of this study are presented as follows. First, I briefly state the various triggers of the Syrian civil war, and indicate the drought’s “threat multiplier” role in the conflict. Second, I provide a review of theoretical literature derived from the environmental security literature, and situate this study in the literature. Third, I provide further development of the argument advanced here. Fourth, I detail the methodology used to test this argument. Fifth, I explain the results of the study’s tests, and provide evidence supporting the argument advanced here. Finally, I conclude the study by restating its central argument and summarizing the evidence presented, notate its implications, address counter-factual reasoning, and state how future research on this topic could be enhanced.

Background: Triggers of the Syrian Civil War

The outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011 derived from a variety of popular grievances directed at Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Calls for an end to martial law, amnesty for political prisoners, and the recognition of a variety of democratic freedoms were some of the early grievances (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 17-18). Additionally, high unemployment (especially among youth) and state decay (Hokayem 2013, 44), as well as income inequality and increasing poverty (Kargin 2018, 28), were factors that contributed to unrest developing. Importantly, it was the regime’s brutality (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 38), use of fear and repression to control people (Kargin 2018, 28), in addition to the state’s overall failure to address popular grievances that set the scene for the 2011 uprising (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 34).

Notably, the state’s neo-liberal economic policies also contributed to the conflict’s onset by increasing unemployment (Hokayem 2013, 10). By cutting state subsidies (Kargin 2018, 37) and redirecting resources to urban communities (Hokayem 2013, 28), the agricultural industry deteriorated (19) which increased unemployment in that sector (Kargin 2018, 39). When the drought occurred, the livelihoods of farmers, particularly in the country’s northeastern governorates, worsened as crop yields and livestock populations plummeted (Gleick 2014, 334). Due to the state’s mismanagement of the drought’s consequences (Hokayem 2013, 19) and overall neglect of rural areas (14), roughly 1.5 million people—most of them unemployed agricultural-sector workers and their families—migrated to southern governorates in search of employment (Gleick 2014, 334).

Resulting from this internal migration was the aggravation of preexisting socioeconomic grievances, particularly in governorates that received an influx of drought refugees (333). The added burden these drought refugees placed on Syrian cities, in particular, helped fuel the spread of rebellion against the Assad regime (Goldstone 2015). Notably, Daraa—a governorate that received an influx of drought refugees—was the site of the initial protests that sparked the onset of the conflict (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 38).

LITERATURE REVIEW: RESOURCE SCARCITY-CONFLICT ONSET NEXUS

Environmental security literature examining the relationship between resource scarcity and conflict onset (resource scarcity theory) informs this study. According to Homer-Dixon et al. (1993), scarcity of renewable resources—in particular water—can lead to the onset of conflicts by instigating displacement and migration, resulting in social disorder (Homer-Dixon et al. 1993, 39). Motivators for scarcity-related migration include constrained agricultural output and resulting economic hardships, such as unemployment (Homer-Dixon and Blitt 1998, 10). Social disorder related to water scarcity, moreover, stems from problems related to the distribution and access of resources within urban areas, in addition to the irresponsiveness of governments in addressing migration-related grievances (10).

Considering the relationship between water scarcity and conflict onset, Swain (2015) argues that water resources have the potential to cause or contribute to the origination or intensification of conflict as a result of tensions related to accessing and consuming water resources (Swain 2015, 443). However, Swain and Jägerskog (2016) note that while water scarcity itself has the potential to precipitate conflict, the degree of efficiency of water management practices and governance can impact the water scarcity-conflict nexus (Swain and Jägerskog 2016, 66). Poor water management practices, then, can also contribute to water scarcity and thus play a role in contributing to unrest.

In the context of periods of drought, Buhaug et al. (2011) explains that water scarcity resulting from significant deviations from normal precipitation levels will have a negative impact on rain-fed agrarian societies by reducing agricultural output (Buhaug et al. 2011, 86). With a sudden drop in the supply of resources, including crops and livestock, subsistence-based populations may be forced to migrate (85). Migration, then, may incite violent conflict through, for instance, triggering competition over resources between migrants and native populations (85).

Concerning the argument advanced in this study, Homer-Dixon et al.’s (1993) theory that resource scarcity can lead to economic hardships (such as unemployment) that precipitate migration, which in turn can result in social disorder stemming from problems related to the accessibility of water resources, informs the theoretical claim advanced here. Essentially, the claim being that drought-induced water scarcity encouraged pre-civil war rural-to-urban migration as a result of its heightening of agricultural-sector unemployment in Syria, which in turn resulted in the aggravation of grievances related to water scarcity partly in the domain of water accessibility.

Moreover, Buhaug et al.’s (2011) claim that rain-fed agrarian societies will experience a reduction in agricultural output due to significant deviations in normal precipitation levels provides support for the claim advanced in this study concerning the drought’s adverse impact on the agricultural-sector in northeastern Syria. Additionally, his theory that drought-induced migration can instigate conflict due to intensified resource-competition is consistent with the claim this study advances, which is that drought-induced migration led to the urbanization of southern governorates. This urbanization, in turn, had the subsequent effect of aggravating existing grievances over water scarcity due in part also to greater competition for water resources among the growing population.

Furthermore, enhancing the theory advanced here concerning the proposed relationship between water scarcity and the onset of initial protests, Swain and Jägerskog’s (2016) argument that improper water management and governance can contribute to water scarcity highlights the potential role that government can play in aggravating grievances over water scarcity. In relation to this study, recognizing the role that government-sponsored water management policies also had in aggravating grievances over water scarcity will assist in addressing how government actions contributed to the outbreak of the initial protests of the conflict.

Essentially, this study seeks to contribute to this body of literature by applying the resource scarcity-conflict onset nexus to the case of the Syrian civil war in order to advance the argument that drought can contribute to the onset of conflicts through a consequence of its heightening of agricultural-sector unemployment—that being the aggravation of grievances over water scarcity.

THEORY AND ARGUMENT

Situating this study in the existing literature, the central argument advanced here is that the drought increased unemployment in the agricultural-sector, and this resulted in the aggravation of preexisting grievances over water scarcity, which assisted in triggering the conflict’s initial protests. As a result of rising agricultural-sector unemployment, rural-to-urban migration ensued, which in turn led to the urbanization of southern governorates. Experiencing water scarcity prior to the drought, drought-induced urbanization intensified water scarcity in these southern governorates, which in turn aggravated preexisting grievances over this issue. Partly due to grievances related to water scarcity (which drought-induced urbanization intensified), initial anti-government protests commenced in 2011, which led to the eventual outbreak of civil war. Thus, through a pathway, the drought contributed to the conflict’s onset as a “threat multiplier” by intensifying a grievance that was a trigger of the initial protests—water scarcity.

DATA AND METHODS

Quantitative Approach

This study’s quantitative analysis portion utilizes data measured at both the aggregate (national)-level and individual (governorate)-level, and displays the results of each test done in the form of descriptive statistics. The timeframe being considered in this analysis is the 2000-2010 period, which comprises the pre-drought (2000-2005) and drought (2006-2010) periods.

Aggregate (National)-Level Analysis

Data was collected from The World Bank Group’s World Development Indicators dataset for Syria on two variables for the pre-drought and drought periods: the country’s (1) agricultural-sector employment rate, and (2) average yearly precipitation levels.

The key independent variable is Average Yearly Precipitation and the key dependent variable is Agricultural-Sector Employment Rate. The independent variable is how drought is measured, and the dependent variable is how this study attempts to capture agricultural-sector unemployment. Obviously, measuring unemployment in the agricultural-sector would be done best by using a variable such as Agricultural-Sector Unemployment Rate. However, since data on such a variable is unavailable, the next-best variable to use is the dependent variable. Simply, this study understands a decrease in the dependent variable as reflecting an increase in agricultural-sector unemployment, and an increase in the dependent variable as reflecting a decrease in agricultural-sector unemployment.

First, it was attempted to identify the drought’s “exacerbating” effect on agricultural-sector unemployment in Syria by comparing the yearly change in the independent variable and dependent variable in order to see if there is a visible correlation between both variables over the 2000-2010 period. This test was meant to address the following hypothesis:

(1) In a comparison of the pre-drought and drought periods, decreasing precipitation should correlate with decreasing agricultural-sector employment, particularly during the drought period.

Second, to determine if agricultural-sector employment is actually dependent on—rather than simply correlated with—precipitation levels, the relationship between the key variables for the 2000-2010 period was tested. This test was meant to address the following hypothesis:

(1) During the 2000-2010 period, as precipitation decreases, agricultural-sector employment should decrease.

Overall, it was expected that the hypothesis for step one, and step two, would be validated, and thus substantiate the claim that agricultural-sector unemployment increased during the drought period in Syria due to less precipitation.

Individual (Governorate)-Level Analysis

Third, using governorate-level data collected from the Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics for the drought period (2006-2010), the yearly distribution of the number of persons unemployed in the agricultural-sector in a northeastern governorate particularly hard-hit by the drought (Al-Hasakah) was tested. It was expected that the number of persons unemployed in this sector rose during this period, and also that this number fell at some point. The logic undergirding this reasoning is that since rural-to-urban migration occurred during the drought period, the number of jobless agricultural-sector workers in this governorate would fall at some point not because employment in this sector was increasing in the governorate, but rather because these unemployed persons were migrating to southern governorates in search of employment—what can be termed “out-migration.” Thus, this test is supposed to lend support for the rural-to-urban migration claim advanced here.

Fourth, the yearly distribution of the urban population for a southern governorate (Daraa) that received an influx of drought refugees, and was a site of initial protests—notably the protests that sparked the onset of the conflict—was tested to see whether during the drought period (2006-2010) if the governorate’s urban population was rising. It was expected that it did, particularly because of its urbanization resulting from its intake of drought refugees, which stems from the out-migration of jobless agricultural-sector workers from northeastern governorates—such as Al-Hasakah. This test is meant to provide support for the claim that drought-induced rural-to-urban migration resulted in the urbanization of southern governorates.

Qualitative Approach

Primarily by using existing scholarly field research and conducted unstructured interviews, in addition to journalistic sources and previous research findings, qualitative data is provided to attempt to support the findings of the quantitative tests, and link the results of each test in a systematic way in order to coherently trace the components of the argument. Importantly, this study focuses on uncovering the impact the drought had on sparking the conflict’s onset by aggravating preexisting grievances over water scarcity in the governorate of Daraa, since it was Daraa’s initial protests that sparked the onset of the civil war.

Due to the lack of accessible quantitative data on water scarcity in Daraa, this study relies on qualitative sources to (1) support the claim that water was a scarce resource in the governorate prior to the drought’s onset; (2) support the claim that drought-induced migration led to the urbanization of Daraa; (3) indicate how drought-induced urbanization aggravated preexisting grievances over water scarcity in Daraa; (4) support the claim that water scarcity was a trigger of the governorate’s initial protests, and that drought-induced urbanization intensified this trigger; and (5) to explain that Daraa’s protests sparked the onset of the conflict.

Consistent with the experiences of other scholars (Cane et al. 2015; Dahi et al. 2017; Gleick 2014), this study encounters methodological obstacles and attempts to overcome them as best as possible using available data. Improving upon existing methodologies is a primary goal of this research.

STUDY RESULTS

Drought and Agricultural Sector Unemployment

According to Figure 1, which displays the results of the hypothesis for the first step of the quantitative analysis, decreasing precipitation in Syria generally correlates with decreasing agricultural-sector employment, particularly during the drought period—except for the year 2009. Notably, from 2006-2008, decreasing precipitation correlates with a steep reduction (roughly 5%) in agricultural-sector employment, which provides support for the first hypothesis. However, Figure 1 also shows that while a mostly positive relationship between precipitation and agricultural-sector employment is visible in the pre-drought period, the drought period witnesses the lowest amount of precipitation and the greatest decrease in agricultural-sector employment. Answering the criticism of scholars (Dahi et al. 2017) concerning the lack of Syria-specific precipitation data in previous research, Figure 1 provides this data.

Figure 2, which displays the results of the hypothesis for the second step of the quantitative analysis, shows that as precipitation decreases in Syria, agricultural-sector employment also decreases, which provides support this step’s hypothesis. Although, Figure 2 also shows that agricultural-sector employment decreases when precipitation rises to a certain amount, which contradicts the reasoning advanced here that agricultural-sector employment should decrease (meaning an increase in unemployment in this sector) when precipitation decreases—not when precipitation increases.

Essentially, the data displayed in Figures 1 & 2 lends support for the claim that the drought increased agricultural-sector unemployment, and qualitative data buttresses their findings. An abnormal reduction in precipitation between 2006-2010 (Gleick 2014, 332), caused by the drought, exacerbated existing agricultural insecurity and resulted in severe agricultural failures and livestock mortality (Cane et al. 2015, 3241). Northeast Syria, in particular, experienced unprecedentedly low rainfall specifically during the 2007-2008 period (Dahi et al. 2017, 234). Low rainfall, then, coupled with reduced water supply (due in part to unsustainable state-administered irrigation policies) caused farmers to lose their employment as a result of decreasing crop yields and their land becoming uncultivable (Cane et al. 2015, 3241). In northeastern governorates including Al-Raqqah, Al-Hasakah, and Deir ez-Zor, rising unemployment in the agricultural-sector forced unemployed farmers and their families to migrate in search of jobs (Worth 2010; Gleick 2014, 336).

Rural-to-Urban Migration

As Figure 3 shows, the number of people unemployed in the agricultural-sector in

Al-Hasakah rose significantly when precipitation was lowest during the 2007-2008 period in this governorate (Dahi et al. 2017, 234). From Al-Hasakah alone, 40-60,000 families migrated in a single year (Ali 2010, 7). One migrant from this governorate recalled that when the drought hit, farmers in the governorate were forced to migrate in order to find work (Friedman 2013). Essentially, coupled with the adverse impact of the state’s reduction in agricultural subsidies prior to the drought’s onset (De Châtel 2014, 526), the drought triggered a migration of jobless agricultural-sector workers from Al-Hasakah and other northeastern governorates notably in 2008 (Mohtadi 2012). The steep decrease from 2008-2010 in the number of jobless agricultural-sector workers in Al-Hasakah, as reflected in Figure 4, supports the claim that out-migration occurred from this and other northeastern governorates in 2008 and continued into 2010 (Dahi et al. 2017, 238-239). Thus, the expectation for step three is supported.

One destination for rural migrants from Al-Hasakah governorate was the governorate of Daraa, which experienced an influx of drought refugees (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 38). Based on the assessment of a Syrian government official in 2008, the increase in rural-to-urban migration resulting from the drought would serve to multiply existing social and economic pressures underway in southern governorates that were experiencing an influx of drought refugees (Public Library of U.S. Diplomacy 2008).

Urbanization

Figure 4 shows the yearly distribution of Daraa’s urban population for the drought period (2006-2010). As the graph depicts, there was an overall steady increase in Daraa’s urban population during the drought period. Specifically from 2008-2010, the urban population increased and continued to rise going into 2010. Notably, given the steep decrease in the number of unemployed agricultural-sector workers in Al-Hasakah during the 2008-2010 period—as Figure 3 depicts—the steady increase in Daraa’s urban population during the same time period lends support for the claim that drought-induced out-migration led to the urbanization of Daraa.

In their search for work, unemployed agricultural-sector workers from Al-Hasakah (De Châtel 2014, 525; Friedman 2013) and other northeastern governorates in the Jazeera region moved to Daraa, which was an already overcrowded governorate (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 33). Given that high population growth rates and accelerated urbanization increased pressure on water resources throughout Syria during the drought period (Barnes 2009, 514), Daraa was one of the governorates to have additional pressure placed on its already scarce water resources due to drought-induced urbanization (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 33).

Conflict Onset

Prior to the drought occurring, water was a scarce resource in Daraa, as it had suffered severe water shortages for years previously (Femia and Werrell 2012; Robins and Fergusson 2014, 7). Due in part to the spread of unregulated wells (Leestma 2017), the resulting over extraction of groundwater led to the depletion of water resources over time (Arnold 2013). Adding to this reduction in available water supply was the drying of surrounding water basins, including the largest natural body of water in the governorate (Lake Muzayrib) that supplied Daraa’s population with drinking water (Leestma 2017). Moreover, the local governor of Daraa had in place a system of water allocation and well-drilling policies that was corrupt and characterized in large part by nepotism, which further contributed to water scarcity (Leestma 2017; Robins and Fergusson 2014, 7). Given the persistence of water shortages, water scarcity was a grievance in Daraa, and state and local government officials did not address this issue (Femia and Werrell 2012; Robins and Fergusson 2014, 7).

When the drought began, water became an even more scarce resource in Daraa because of drought-induced urbanization. Receiving an influx of migrants from Syria’s northeast, there was a proliferation of illegal well drilling by migrants as they, along with Daraa’s residents, extracted groundwater to use (Arnold 2013). Rapid population growth in turn led to the increased usage of already limited water resources, which also resulted in greater competition for water (Femia and Werrell 2012). Thus, preexisting water scarcity grievances were aggravated further due to intensified water scarcity resulting from drought-induced urbanization, and the state again did not respond effectively to address the issue (Cane et al. 2015, 3242).

Although often overlooked, this aggravation of water scarcity grievances contributed to the civil war’s onset. In March 2011, the initial protests that sparked the onset of the conflict began in Daraa, and were initiated mainly in response to the police’s arrest and torture of fifteen schoolboys who had been caught writing revolutionary slogans on the walls of their school (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 38). However, Daraa’s protests commenced also in response to grievances related to water scarcity—which drought-induced urbanization intensified. Notably in the domain of well licensing and groundwater usage (De Châtel 2014, 525), Daraa’s population took to the streets to also protest the nepotism and corruption characterizing the Ministry of Agriculture’s groundwater irrigation and well-licensing practices (Leestma 2017). Unrest over the local governor’s corrupt allocation of scarce water resources encouraged mobilization as well, with it even being suggested that the reason why the fifteen schoolboys sprayed anti-regime graffiti was in response to their anger over the governor’s corrupt water management practices (Fergusson 2015).

In response to the security force’s violent crackdown of Daraa’s protesters, anti-Assad demonstrations were subsequently initiated throughout Syria as people rose up in solidarity with Daraa’s citizens (Al-Shami and Kassab 2016, 39). As demonstrations spread nationally, the state responded with increasingly brutal force, and civil war eventually broke out. Importantly, by aggravating preexisting grievances over water scarcity in Daraa by intensifying water scarcity, the drought contributed to the conflict’s onset—as a threat multiplier—since it intensified a preexisting grievance (water scarcity) that was a trigger for the outbreak of the initial protests that sparked the onset of the conflict.

CONCLUSION: DROUGHT AS A THREAT-MULTIPLIER

In effect, this study lends support for the argument that the pre-civil war drought contributed to the onset of the Syrian civil war as a “threat multiplier”, specifically through a sequence of events. Essentially, the drought increased unemployment in the agricultural-sector, and this resulted in the aggravation of preexisting grievances over water scarcity, which was a trigger of the conflict’s initial protests—notably the initial protests that sparked the onset of the conflict.

In light of the puzzle concerning how environmental stresses contribute to the onset of intrastate conflicts, and specifically how a type of environmental variable—drought—contributed to the onset of the Syrian civil war, this study both illuminates a specific pathway through which environmental factors can play a role in triggering intrastate conflicts, and highlights the applicability of the resource scarcity-conflict onset nexus to the Syrian civil war.

It should be noted that the argument advanced here is challenged by counterfactual reasoning, which warrants recognition for its legitimacy. As the starting point for this study’s argument, it is claimed that the 2006-2010 drought is the reason why agricultural-sector unemployment increased in Syria’s northeast during the drought period. Contradicting this claim, other scholars (Dahi et al. 2017) argue that the drought is an insufficient explanation for why unemployment in this sector increased. Rather, the rise in unemployment is argued to be due to consequences stemming from the dramatic economic transformations that Syria had been undergoing prior to and during the drought period in its push towards market liberalization (238).

Specifically, in transitioning towards a competitive market economy, the state cancelled or reduced number of subsidies it had traditionally provided to farmers in order to subsidize their employment activities. When those subsidies were curtailed during the drought period, thousands of agricultural-sector workers lost their jobs as they could no longer sustain their farming activities in the face of rising prices for important agricultural inputs—which they could no longer afford due to reduced state support (238). Thus, the increase in agricultural-sector unemployment is better explained by the consequences of Syria’s economic liberalization policies rather than the drought’s onset. This is a valid claim, as there is quantitative and qualitative evidence to support it. Future research would benefit from quantifying a measure of “economic liberalization” and using regression analysis to test its statistical significance, relative to the drought, in determining changes in agricultural-sector unemployment.

Additionally, contrary to the claim advanced here, it is even argued that water scarcity was not a trigger of Daraa’s initial protests (240). Essentially, it is claimed that protests commenced in response to grievances related to specifically civil rights and political freedoms (240). Given the conflicting claims advanced, future research would benefit from undertaking a further examination of the reasons behind Daraa’s protesters taking to the streets—such as through in-depth interviews with Daraa’s residents—in order to assess the centrality of water scarcity as an issue for Daraa’s citizens.

Overall, this study adds to existing scholarly literature dedicated to untangling the complex role that a drought played in sparking the onset of the Syrian civil war. It is the hope of the author that this research sparks further scholarly debate on the topic, as further examination is warranted.

Daniel Hurley is a senior at The College of New Jersey where he studies Political Science.

References

Al-Shami, Leila and Robin Yassin-Kassab. 2016. Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War. London: Pluto Press.

Ali, Massoud. 2010. Years of Drought: A Report on the Effects of Drought on the Syrian Peninsula. Beirut: Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Accessed 16 October, 2018. https://lb.boell.org/sites/default/files/uploads/2010/12/drought_in_syria_en.pdf.

Arnold, David. 2013. “Drought Called a Factor in Syria’s Uprising.” VOA News, August 20, 2013. https://www.voanews.com/a/drought-called-factor-in-syria-uprising/1733068.html.

Barnes, Jessica. 2009. “Managing the Waters of Ba’th Country: The Politics of Water Scarcity in Syria.” Geopolitics 14, no. 3 (August): 510-530.

Buhaug, Halvard, Helge Holtermann, and Ole Magnus Theisen. 2011. “Climate Wars?: Assessing the Claim That Drought Breeds Conflict.” International Security 36, no. 3 (Winter): 79-106.

Cane, Mark A., Colin P. Kelley, Yochanan Kushnir, Shahrzad Mohtadi, and Richard Seager. 2015. “Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 11 (March): 3241-3246.

Dahi, Omar S., Christiane Frohlich, Mike Hulme, and Jan Selby. 2017. “Climate change and the Syrian civil war revisited.” Political Geography 60, (March): 232-244.

De Châtel, Francesca. 2014. “The Role of Drought and Climate Change in the Syrian Uprising: Untangling the Triggers of the Revolution.” Middle Eastern Studies 50, no. 4 (January): 521-535.

Femia, Francesco and Caitlin Werrell. 2012. “Syria: Climate Change, Drought and Social Unrest.” The Center for Climate & Security, https://climateandsecurity.org/2012/02/29/syria-climate-change-drought-and-social-unrest/.

Fergusson, James. 2015. “The World Will Soon be at War Over Water.” Newsweek, April 24, 2015. https://www.newsweek.com/2015/05/01/world-will-soon-be-war-over-water-324328.html.

Friedman, Thomas L. 2013. “Without Water, Revolution.” Interview by Thomas Friedman. New York Times, May 18, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/19/opinion/sunday/friedman-without-water-revolution.html.

Gleick, Peter H. 2014. “Water, Drought, Climate Change and Conflict in Syria.” American Meteorological Society 6, no. 3 (July): 331-340.

Goldstone, Jack A. 2015. “Syria, Yemen, Libya – one factor unites these failed states, and it isn’t religion.” Reuters, November 30, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/goldstone-climate/column-syria-yemen-libya-one-factor-unites-these-failed-states-and-it-isnt-religion-idUSL1N13P2HJ20151130.

Hokayem, Emile. 2013. Syria’s Uprising and the Fracturing of the Levant. London: Routledge.

Home-Dixon, Thomas, Jeffery H. Boutwell, and George W. Rathjens. 1993. “Environmental Change and Violent Conflict: Growing Scarcities of Renewable Resources Can Contribute to Social Instability and Civil Strike.” Scientific American (February): 38-45.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas and Jessica Blitt. 1998. Ecoviolence: Links Among Environment, Population, and Security. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kargin, İnci Aksu. 2018. “The Unending Arab Spring in Syria: The Primary Dynamics of the Syrian Civil War as Experienced by Syrian Refugees.” Turkish Studies 13, no. 3 (Winter): 27-48.

Leestma, David. 2017. “Draining a lake in Daraa: How years of war caused Muzayrib to dry up.” Middle East Eye, October 1, 2017. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/draining-lake-daraa-how-years-war-caused-lake-muzayrib-largely-disappear-1202640340.

Mohtadi, Shahrzad. 2012. “Climate change and the Syrian Uprising.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 16, 2012. https://thebulletin.org/2012/08/climate-change-and-the-syrian-uprising/.

Public Library of U.S Diplomacy. 2008. “2008 UN Drought Appeal for Syria.” Action Request Cable. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08DAMASCUS847_a.html.

Robins, Nicholas S. and James Fergusson. 2014. “Groundwater scarcity and conflict – managing hotspots.” Earth Perspectives 1, no. 6 (January): 2-9.

Suter, Margaret. 2017. “Running Out of Water: Conflict and Water Scarcity in Yemen and Syria.” Atlantic Council, September 12, 2017. http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/running-out-of-water-conflict-and-water-scarcity-in-yemen-and-syria.

Swain, Ashok and Anders Jägerskog. 2016. Emerging Security Threats in the Middle East: The Impact of Climate Change and Globalization. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Swain, Ashok. 2015. “Water Wars.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by James D. Wright, 443-447. Oxford: Elsevier.

Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2006-2010. Force Lab. Damascus: Office of the Prime Minister. http://www.cbssyr.sy/index-EN.htm.

World Bank. 2000-2010. Database: Syrian Arab Republic. https://data.worldbank.org/country/syrian-arab-republic.

World Bank. 2001. World Bank Development Indicators. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Worth, Robert F. 2010. “Earth Is Parched Where Syrian Farms Thrived.” New York Times, October 13, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/14/world/middleeast/14syria.html.